Introduction to R Markdown

Data Visualization

Johan Larsson

2022-08-25

1 A Syntax for Writing Documents

This document is written using R Markdown. R

Markdown is a syntax for formatting documents that lets you focus on content.

You write text (including R code) in a standard text document with the ending

.Rmd and then your machine turns your text into a neatly formatted document.

In addition, R Markdown documents can be compiled into a wide variety of formats, including PDFs, Word Documents, and HTML pages (and much more) without having to change the content on your document.

This document has in fact been rendered as both a PDF document and html page. You can choose any of these when following this guide, but we recommend reading the PDF version to get a sense of what your output actually will look like (since you’ll be handing in PDF documents in this course).

Authoring your documents using R Markdown facilitates reproducibility. Because

you need to supply all the code used to produce your paper in the .Rmd file,

this makes it much easier for other people to re-run your analysis and use your

code. It also means that your paper is now automated. Should you need to update

or modify your data, for instance, you will typically be able to generate your

final document simply by re-knitting it after having made your changes.

As you proceed though this document, consider taking a look at the R Markdown source code for this document too, to get a better feel for what R Markdown documents look like.

2 Getting Started

2.1 Installation

To get started, you are going to need two packages: rmarkdown and knitr.

Run the following line of code to install these now. If you happen to be looking

at the source

code

as you read this, you can simply highlight the text and hit Ctrl/Cmd + Enter

or put the cursor inside the code chunk below and hit Ctrl/Cmd + Shift + Enter

to run the command (and install the packages).

install.packages(c("rmarkdown", "knitr"))To produce PDF documents, you will also need a distribution of LaTeX. Installing LaTeX is fortunately easy using the tinytex package. Do so now (unless you already have a working installation of LaTeX on your computer) by calling the following lines of code.

install.packages("tinytex")

tinytex::install_tinytex()After this, we also recommend that you set the options in Tools > Global Options > Sweave in R Studio as in Figure 1.

Suggested global options in R Studio.

2.2 Your First R Markdown Document

For this course, we have provided a R Markdown template that provides better defaults for your documents than the built-in one. You can download it your current working directory in R by calling the following lines.

download.file(

"https://raw.githubusercontent.com/stat-lu/dataviz/main/resources/template.Rmd",

"template.Rmd", # destination, you can replace this if you want

mode = "wb"

)Then open the template.Rmd file in RStudio.

2.3 Knitting

Now that you have LaTeX installed, you can turn the R Markdown template into a

PDF by knitting it. To do so in R Studio, simply hit Ctrl/Cmd + Shift + k

with the file open. Doing so will tell R to run through all of your code blocks

and text and pass this on to LaTeX to render your document into a PDF file,

which should open up on your screen.

3 YAML block

Each R Markdown file starts with a so called YAML block, such as this one:

---

title: "An Awesome Title"

author: "Fantastic Me"

date: "2020-09-28"

output: pdf_document

---The YAML block contains settings that control the title block (title, author,

date) and options for the layout. For this course, please use the YAML block

supplied in the template, modifying only the author and title fields. (The

date field in the template adds the current date automatically.)

4 Formatting

R Markdown is an extension of Pandoc Markdown, which uses a special—but very simple—syntax for formatting text.

First of all, a contiguous block of text is treated as a paragraph. Separate paragraphs with blank lines. Formatting text in italics, bold font, or monospace (fixed-width) fonts is accomplished by wrapping text with symbols (Table 1).

| Markdown | Output |

|---|---|

*italics* |

italics |

**boldface** |

boldface |

typewriter (monospace) |

typewriter (monospace) |

4.1 Sections

Sections are created by prefacing the section title with a hash tag (#).

# One Hashtag Creates a Section

## Two Hashtags Creates a Sub-section

### Three Hastags Creates a Sub-sub-section

In Figure 2, we show what this looks like.

Sections in R Markdown

4.2 Lists

To create (unnumbered) lists in markdown, add a

- dash before each item in the list, and

- indent each sub-item with two spaces.

* If you prefer, you can also use asterisks, and

+ plus signs (or a mix).The output looks like this:

- dash before each item in the list, and

- indent each sub-item with two spaces.

- If you prefer, you can also use asterisks, and

- plus signs (or a mix).

Ordered lists are

1. created similarly, but

2. use numbers or letters instead of dashes.

a) It's easy to add sub-items too!The output looks like this:

- created similarly, but

- using numbers or letters instead of dashes.

- It’s easy to add sub-items too!

4.3 Tables

There are many ways to format tables in

markdown, but the simplest one is to simply create columns of text with dashes

(---) separating the title of each column from the cells of the table.

Table: A caption for the table can be added like this.

Header 1 Header 2

--------- ---------

Cell 1 Cell 2

Cell 3 Cell 4Table 2 shows what the output looks like.

| Header 1 | Header 2 |

|---|---|

| Cell 1 | Cell 2 |

| Cell 3 | Cell 4 |

4.4 Links

To add a link in Markdown, you can either simply surround the URL with angled

brackets (<>) or square brackets ([]) and parentheses (()) if you

want to replace the URL with a label (Table 3).

| Markdown | Output |

|---|---|

<https://stat.lu.se> |

https://stat.lu.se |

[Link](https://stat.lu.se) |

Link |

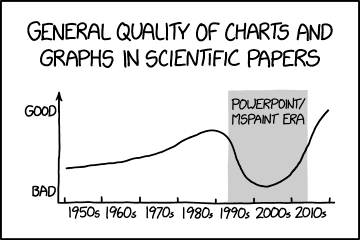

4.5 Images

Images can be added with syntax similar to the one for links, with the text

inside brackets indicating the caption for the figure. Provided that

we have stored a figure at images/xkcd.png, we can include it like this.

{width=300px}Note the use of the exclamation mark at the start of the

code as well as the use of {width=300px} here to

specify the width of the image. The result is available in Figure 3.

A caption (https://xkcd.com/1945/).

4.6 Footnotes

Footnotes can be useful to provide additional information. To create

a footnote, the simplest way is to write ^[Footnote], like this:

This sentence has a footnote^[Additional information].

In the output, it shows up like this:

This sentence has a footnote1.

4.7 Citations

It is possible to add citations in R Markdown but this is somewhat complicated if you are not familiar with Markdown and Pandoc. You will not be needing a lot of (or even any) references in this course, so it’s perfectly alright to write your references and citations manually; in this case, you can skip the next paragraph.

To cite in R Markdown, you will need either 1) a .bib file (with

BibTeX-formatted references) somewhere in your working directory or 2) a

references field in the YAML block, like the following:

references:

- id: wickham2010

title: A Layered Grammar of Graphics

author:

- family: Wickham

given: Hadley

issued:

year: 2010

month: 1

container-title: Journal of computational and graphical statistics

volume: 19

issue: 1

page: 3-28

DOI: 10.1198/jcgs.2009.07098

URL: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1198/jcgs.2009.07098

type: article-journalUsing a .bib file is recommended unless you only have a few references.

To cite something, find the key of the reference you are looking for—in this case

wickham2010—and preface it with an @. See the examples in Table 4.

| Type | Markdown | Output |

|---|---|---|

| text citation | @wickham2010 |

Wickham (2010) |

| indirect deference | [@wickham2010] |

(Wickham 2010) |

If you’ve done everything right, the final document will get a bibliography at the end (as in this one).

5 Code Chunks

So far we’ve only really talked about features that are included in vanilla Markdown2. But what makes R Markdown special is that is allows us to include chunks of R code in our texts, have them be evaluated, and their output included in the final document. Here is a simple example of a code chunk.

``{r}

x <- 3 + 9

x

```When we knit our document, the output looks like this:

x <- 3 + 9

x## [1] 12As you can see, we’ve started the code chunk with ```{r} and ended it with ```. Everything in between will be treated as R code, just as if you would

have written in in an R script or the R terminal. When you compile this

document, all this code will be run and if it produces any output (text, plot,

tables) then that output will make it into the final document. In addition,

all the code you include will receive pretty syntax highlighting.

5.1 Figures

The primary reason for why R Markdown is so useful in this course is as a means of getting our visualizations into a document. To produce a visualization in R Markdown, simply write the code as you would have otherwise, knit the document, and watch the magic happen. Here’s an example.

``{r chode-chunk-label}

library(tidyverse)

ggplot(msleep, aes(brainwt, sleep_rem)) +

geom_point() +

scale_x_log10() +

labs(x = "Brain Weight (lbs)", y = "REM Sleep (hours)")

```The result is the formatted code and the figure.

library(tidyverse)

ggplot(msleep, aes(brainwt, sleep_rem)) +

geom_point() +

scale_x_log10() +

labs(x = "Brain Weight (lbs)", y = "REM Sleep (hours)")The header of the code chunk (everything between {r and }) can be used to

specify settings that control the behavior and output of the code. The first

word after r is treated as the label of the code chunk. You don’t need to

use labels at all3. In particular, when we generate figures, the

fig.width, fig.height, and fig.cap options to set the dimensions of the

resulting figure as well as its caption.

In the following code chunk, we’ve used this to modify the size of the figure and to add a descriptive caption.4

``{r brain-figure, fig.cap = "Brain weight and REM sleep

duration for mammals.", fig.width = 4, fig.height = 1.5, echo = FALSE}

ggplot(msleep, aes(brainwt, sleep_rem)) +

geom_point() +

scale_x_log10() +

labs(x = "Brain Weight (kg)", y = "REM Sleep (hours)")

```Figure 1: Brain weight and REM sleep duration for mammals.

You can see the finished result in Figure 4.

5.2 Tables

We’ve previously covered how to write tables in Markdown, but it’s also possible

to use R Markdown to create tables directly from code and objects in R using

knitr::kable() (or kableExtra::kbl(), which is identical to the former

command but better documented).

Let’s, for instance say we wanted to show the first few rows of some of the

variables in the mpg data set. Then we could do the following:

``{r kable-example, echo = FALSE}

library(ggplot2)

mpg %>%

head(8) %>%

select(1:6) %>%

kableExtra::kbl(

caption = "The first observations of the `mpg` data set.",

booktabs = TRUE # nicer tables for PDF output

)

```| manufacturer | model | displ | year | cyl | trans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| audi | a4 | 1.8 | 1999 | 4 | auto(l5) |

| audi | a4 | 1.8 | 1999 | 4 | manual(m5) |

| audi | a4 | 2.0 | 2008 | 4 | manual(m6) |

| audi | a4 | 2.0 | 2008 | 4 | auto(av) |

| audi | a4 | 2.8 | 1999 | 6 | auto(l5) |

| audi | a4 | 2.8 | 1999 | 6 | manual(m5) |

| audi | a4 | 3.1 | 2008 | 6 | auto(av) |

| audi | a4 quattro | 1.8 | 1999 | 4 | manual(m5) |

The result is shown in Table 5.

5.3 Other Chunk Settings

There are a few other code chunk settings that

are useful to know about, namely echo, eval, and include.

Here are some examples of these arguments (note that echo = TRUE, eval = TRUE, and include = TRUE are the defaults and hence need not be specified

unless we want to change them):

Use echo = FALSE when you want to hide the code but evaluate it

and show all output (like figures).

``{r echo = FALSE}

print("Hello World!")

```## [1] "Hello World!"Use eval = FALSE when you want to show code but not have it be evaluated.

``{r eval = FALSE}

print("Hello World!")

```print("Hello World!")Use include = FALSE if you want the code to be evaluated but hide all output

(including figures).

``{r include = FALSE}

print("Hello World!")

```5.4 Global Chunk Settings

The chunk settings (defaults) for an R Markdown document can be modified

globally. To do so, you need to call the knitr::opts_chunk$set() function at

the top of your document. Inside the function, you set defaults for the various

chunk arguments. The following are the global settings for the template.

``{r setup, include = FALSE}

knitr::opts_chunk$set(

echo = FALSE,

warning = FALSE,

message = FALSE,

fig.align = "center",

fig.width = 2.5,

fig.height = 2.2

)

```We use the settings echo = FALSE, include = TRUE, and eval = TRUE (the

latter two are the defaults so need not be specified) so that, by default, all

output, including figures, are shown in the document but no code.

The reason we use these defaults is that you most often will not

include your code in this course. It’s easier then to use echo = TRUE

directly whenever you do need to do this.

6 Learning More

If you want to learn more about R Markdown, we recommend the R Markdown

Cookbook. If

you run into any issues with R Markdown, please use the course’s discussion

board on Canvas, search stack overflow with the

[r-markdown] or [knitr] tag, or simply google it.

7 Troubleshooting

Occasionally, there are a few hiccups to get started with R Markdown and they mostly involve the LaTeX installation and computer systems where you as a user don’t have complete administrator rights. Here, we’ve listed a few of these issues and remedies for them.

7.1 Error: '"pdflatex"' not found

If you receive an error when knitting such as the following,

Error: Failed to compile Test.tex.

In addition: Warning message:

In system2(..., stdout = FALSE, stderr = FALSE) : '"pdflatex"' not found

Execution haltedthen please try running tinytex:::install_prebuilt().

If this doesn’t help, take a look at https://github.com/yihui/tinytex/issues/103 to see if any of the suggested solutions there may help.

7.2 Error: /usr/local/bin not writable

If you are on Mac OS X, you may be getting the following error (or something

like it) when trying to run tinytex::install_tinytex():

add_link_dir_dir: destination /usr/local/bin not writable,

no links from /Users/<user>/Library/TinyTeX/bin/x86_64-darwin.

tlmgr: An error has occurred. See above messages. Exiting.In this case, try to run the following commands in your terminal:

sudo chown -R `whoami`:admin /usr/local/binfollowed by

~/Library/TinyTeX/bin/x86_64-darwin/tlmgr path addIf this doesn’t work, have a look at https://github.com/yihui/tinytex/issues/24, where this issue has been discussed.

7.3 I still cannot knit to PDF!

As a last resort, you can change the output from PDF to Word document instead (but then you need to convert it to PDF before submitting).

In this case, change the output section in the YAML front matter to the following:

output:

word_document:

number_sections: trueReferences

Additional information↩︎

To be precise, some of these features actually need Pandoc’s flavor of Markdown to work.↩︎

They are mostly useful if you want to use some advanced features like cross-referencing with the bookdown package, but this is beyond our scope here.↩︎

We’ve inserted a line break into the code chunk header to avoid having it escape into the margin here, but be aware that you cannot actually do this in your code.↩︎